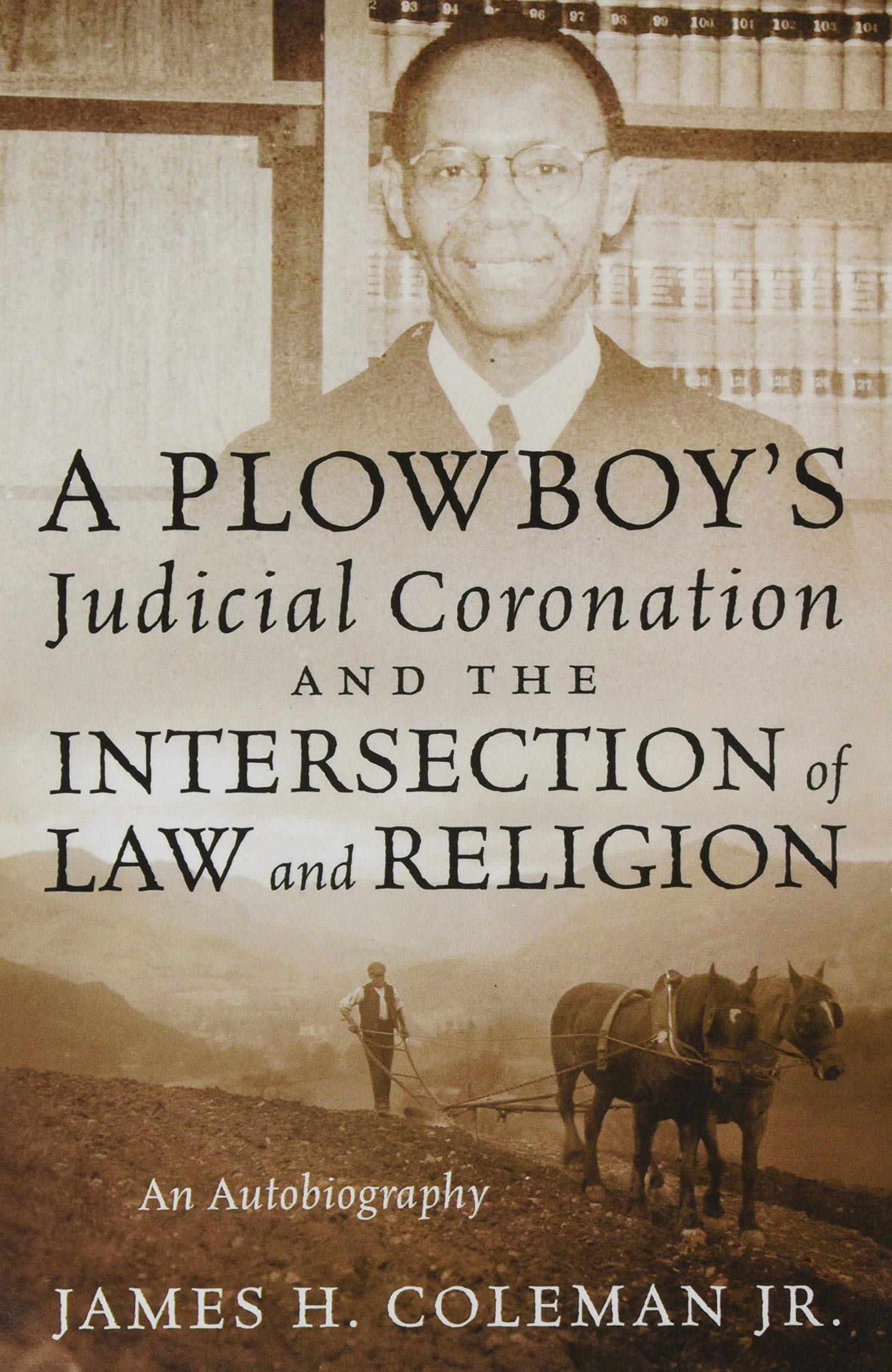

A Plowboy’s Judicial Coronation and the Intersection of Law and Religion: An Autobiography Hardcover 2020 by James H Coleman Jr

HARDCOVER

[248 pages]

PUB:July 30, 2020

Description

This book uses history, literature, and constitutionalism to tell the story about a poor African American male, born to illiterate former sharecropper parents, on the kitchen table of a farm house without electricity or plumbing, with the help of his maternal grandmother’s hands. I was born in Southside Virginia during the Great Depression and the height of racial segregation and white supremacy. This book paints a word picture of my Horatio Alger struggle to obtain an education through the 7th grade and beyond while always striving for excellence in pursuit of my American Dream. Even early pursuit of my American Dream involved conflicts over which of three options I had to pursue: whether to become a Baptist Minister like my childhood church assumed I would, a medical doctor as my mother wished, or a lawyer-judge, a sort of “Secular Minister for Justice.” My conflict was resolved when I realized that all three involved some form of human healing. Part of my early conflict was influenced by the role of the Oak Grove Baptist Church had played during the first 15 years of my life, the role of the Episcopal Church had played in my first two years of high school, the influence of being Assistant Superintendent of Sunday School beginning at age fifteen, and the influence of my mother’s deeply religious beliefs, all of which help to explain the connection between law and religion in my autobiography.

In order to achieve my American Dream of becoming a Secular Minister for Justice, I had to strive to become the first African American to become a Justice on the highest Court in New Jersey, the Supreme Court. Even though New Jersey has had a constitutionally established judiciary since 1776, it was 218 years after establishing a judicial branch of government, 207 years after statehood, and 101 years after the first African American had been admitted to practice law in New Jersey before an African American became a member of the state’s highest Court, the Supreme Court, in 1994. What follows in this book are the recollections of a sharecropper’s son, a snot-nosed, cotton-picking, tobacco-chopping poor boy who became that historical appointee. Despite those circumstances, I believe that the “cup of hope [should not be] dashed untasted from the lips of [people] like me who have not the boast of ancestral privileges.” Adversity helped to make me a humble person and encouraged me to try hard to become a hero in the strife. In the process of trying to succeed despite the adversity, faith, hope and patience became soft cushions to lean on as my support system.

During my 39 year judicial career, I wrote a number of cutting-edge opinions that decided whether an individual’s rights should be protected under the New Jersey or the Federal Constitution. We adopted a cutting-edge principle known as New Jersey Federalism under which the Federal Constitution sets a floor below which an individual’s rights cannot fall and our State Constitution as a ceiling for individual rights.

| Weight | 2 lbs |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 10 × 6 × 1 in |

| Author | |

| Format | |

| ISBN-10 | |

| Language | |

| Publication Date | |

| Publisher |

Be the first to review “A Plowboy’s Judicial Coronation and the Intersection of Law and Religion: An Autobiography Hardcover 2020 by James H Coleman Jr”

You must be <a href="https://webdelico.com/my-account/">logged in</a> to post a review.

There are no reviews yet.